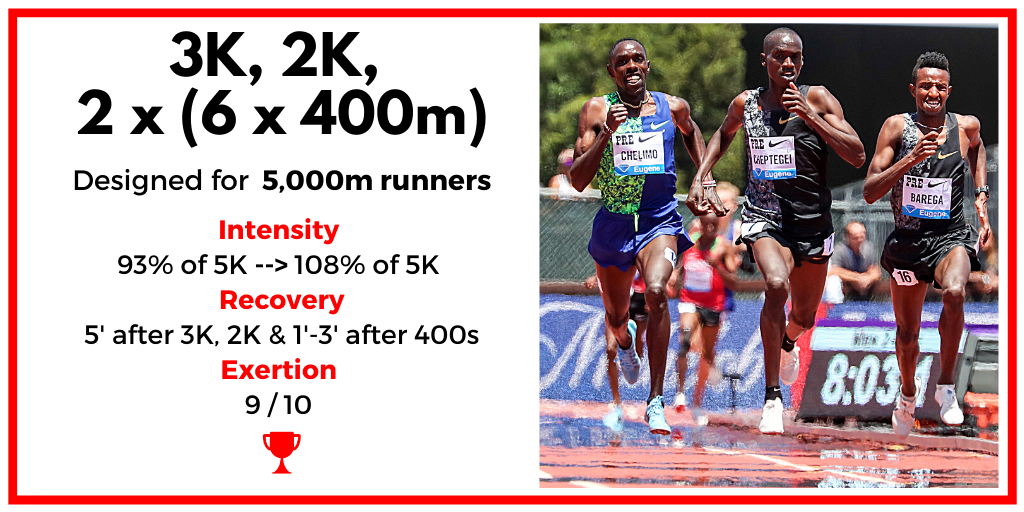

Workout of the Day: 3K, 2K, 2 x (6 x 400m)

3K, 2K, 2 x (6 x 400m)

Intensity — 3,000m @ 93% of 5K, 2,000m @ 95% of 5K, 1st 400m set @ 103% of 5K, 2nd set @ 108% of 5K

Recovery — 5’ after 3K, 2K, and between 400m sets. 1’ after 400s in 1st set, 3’ after 400s in 2nd set

Exertion — 9/10

Context & Details

This is another Canova workout. It was performed by Thomas Longosiwa of Kenya, the 2012 Olympic Games bronze medalist in the 5,000m.

His splits were 8:28 for 3K, 5:25 for 2K, 60” average on the first set of 400s, and 57” average on the final set.

He performed it about a month before the 2011 track & field World Championships. Meaning, this would be a workout designed to take place in the Specific period of training, if we’re using Canova terms.

There’s a lot of math going on in this workout. But at the elite level, coaches and athletes are very sensitive to the tension of pace, density, and duration of reps in an interval workout .

You may wonder how big of a difference 93% vs. 95% of 5K pace is.

For Longosiwa, that’s 67”/400m vs. 65”/400m speed. While 2 seconds doesn’t seem like a lot, at this level it is.

Novice or amateur runners enjoy big gains in improvement with very remedial training methods. But elites are competing at the upper limits of human performance so their gains are disproportionately smaller compared to the incredible amount of intensity and volume of work they do.

There is not much difference between the 4:20 and 4:15 female 1500m runner. There is a little more separation between the 4:15 and 4:10 runner. Bigger distinctions come once the 4:10 barrier is broken. The 4:10 doesn’t make a US championship final, while 4:05 is in the hunt for a top-5 finish. The 4:05 runner has a hard time making a world champs final, while the 4:00 runner is running in the front pack in the final laps of the world final.

At a certain point, every 5 seconds of improvement in a 1500m represents a different world. Same is true for the 5K at the world class level, but in about 10 second (or 1 second per lap) intervals.

As the athlete becomes faster, those seconds are harder to shave off and they become far more pace sensitive. Thus, the need for specific mathematics to determine the athlete-appropriate paces and recovery intervals for a session.

In the 5,000m, resistance to fatigue training is paramount. Chris Solinsky once described the 5K as feeling like being stung by a swarm of bees the entire way. Even if you’re in the best shape of your life and competing at a high level, “an all-out 5K is going to hurt the whole way” as he put it.

The entire race, if the pace is honest, is run at the upper limits of a runner’s VO2 Max, or their vVO2 Max. Practically, this means the runner needs to “get comfortable with being uncomfortable” for 5,000 meters. The only relief in the 5K comes when the race ends. Otherwise it is a concentrated exercise in redlining.

This session upgrades a lot of performance variables concurrently: resistance to fatigue, aerobic power, running economy, VO2 Max, vVO2 Max, lactate-threshold velocity — but most importantly it steadies the mind to embrace the sting felt throughout the entire 12 1/2 laps of racing.